Evading EDR Detection with Reentrancy Abuse

Cybercriminals have developed a diverse toolset to uncover vulnerabilities and repurpose existing software features to find entry points through cyber defenses. In this blog, we’ll explore a new way to exploit reentrancy that can be used to evade the behavioral analysis of EDR and legacy antivirus products.

While the technique we’ll examine focuses on a single-hooked API, this method of evasion can be used against almost any antivirus tool’s hooks by reverse-engineering the AV product to allow a bypass and custom-tailoring the bypass method.

Most antivirus and endpoint detection and response (EDR) products focus on scanning and detection, with some leveraging additional capabilities on top of their file scanning mechanism to detect malicious activity.

One of these capabilities involves tracking processes in-memory through behavioral analysis or heuristics. In short, the antivirus solution will detect or prevent certain behaviors that are deemed to be malicious, such as dumping credentials from memory or injecting code into another process. Finding these malicious activities helps the antivirus software detect a threat that isn’t caught by the file-scanning capability. It is also useful when the file hash is not blacklisted, or the attack is fileless.

In order to find malicious behavior in process, an antivirus product will usually have its own DLL loaded into every process via its signed kernel driver on process startup. Once loaded, this DLL will then place hooks on the APIs that require tracking.

For code injection, kernel32.dll’s functions including “CreateRemoteThread,” “VirtualAllocEx,” and “WriteProcessMemory” will most frequently be used. Most of the time security vendors will prefer to hook the lowest-level API possible, such as hooking “NtWriteVirtualMemory” inside ntdll.dll instead of “WriteProcessMemory.” This is done for programs that do not call the higher-level APIs, which can limit the heuristics’ ability to catch malicious behavior.

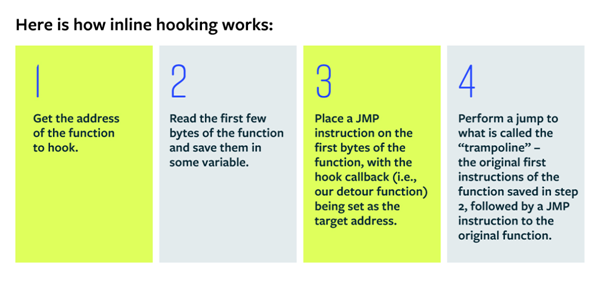

What is Inline Hooking?

Userland hooks is a very popular way for antivirus tools to inspect the behavior of a process. Hooking is the process of intercepting a function call. As the guardian of the endpoint, intercepting calls to various APIs allows the antivirus product to not only detect, but also to prevent unwanted or suspicious activity. This is done most by inline hooking (sometimes known as detouring).

Hooking and Reentrancy

A very common problem that occurs when hooking Windows APIs is reentrancy. This occurs when a thread calls a hooked API, and the hook then calls another hooked API, or even that same hooked API (either directly or indirectly). This process can lead to unnecessary overhead—and can also lead to an infinite recursion.

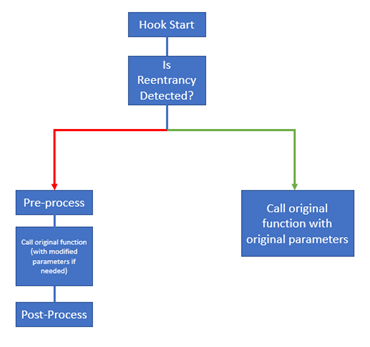

Reentrancy issues are a significant challenge for antivirus tools because using hooks on every single process can cause severe stability issues, freezing, and other performance problems. A common approach to this is to be careful about what code to write in the hook itself and make sure to not call any other API (directly or indirectly); this method limits what behaviors can be monitored. However, a more elegant solution is simply to check for reentrancy. In this approach the hook’s trampoline will be called directly if reentrancy is detected, skipping whatever checks and logic the hook usually goes through in its process.

Below is a diagram to show the flow of a reentrancy-friendly hook:

Technical Explanation

Locating Hooks

For this next section we will play the part of the attacker and walk through the steps that one would take to evade antivirus with one line of code.

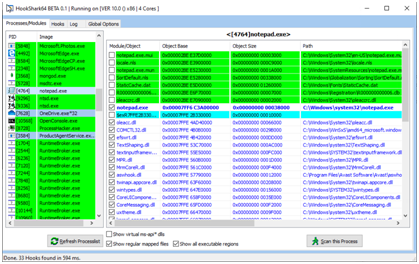

The first step to locate a hook is to determine what APIs are hooked. HookShark is a terrific tool to detect inline hooking. It provides a quick way to find what APIs a security vendor hooks.

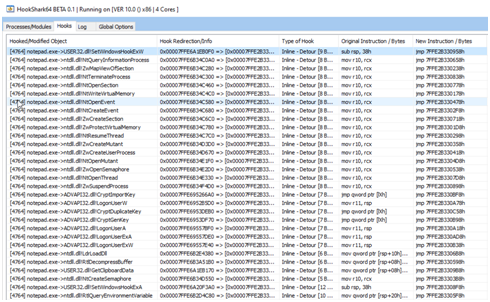

For this example, when Notepad is launched, pressing “Scan this process” shows these results:

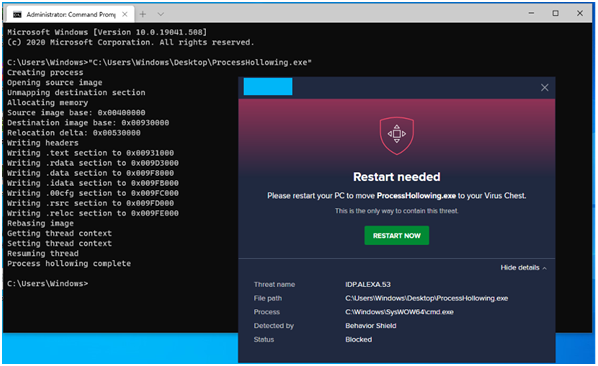

An API that caught our attention is NtWriteVirtualMemory, which is used for process injection techniques. As the attacker, we will determine if the antivirus would detect the attempt at process hollowing (using the project here: https://github.com/m0n0ph1/Process-Hollowing). As we can see, it was detected:

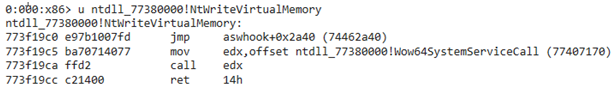

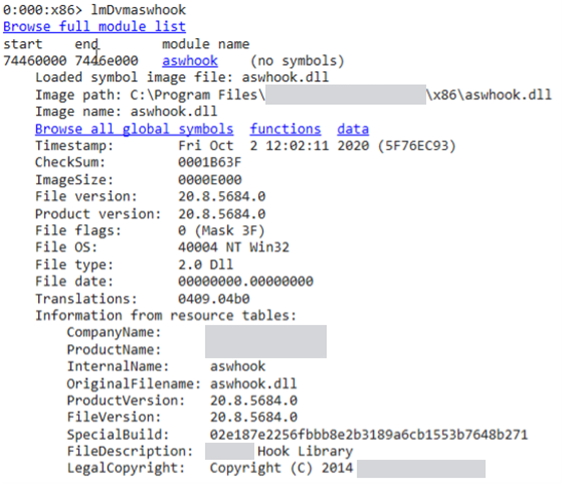

The second step is to determine where the hook sits. Luckily for us, the hook is inside the antivirus’ injected DLL – aswhook.dll.

Disassembling the Hook

Now that we know what file to disassemble, it should be very easy to open IDA and locate the hook.

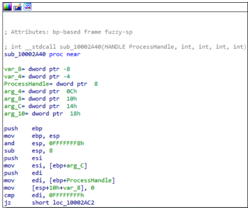

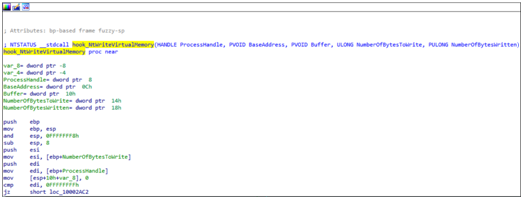

This is the function as seen in IDA:

Now, we know this a hook for the function “NtWriteVirtualMemory,” so this should be what the API looks like:

NTSTATUSNtWriteVirtualMemory(

INHANDLEProcessHandle,

INPVOIDBaseAddress,

INPVOID Buffer,

INULONGNumberOfBytesToWrite,

INOUTPULONGNumberOfBytesWritten);

Now, we can simply change the function’s definition and name:

This will be easier to disassemble now that we know the type definitions of all the arguments.

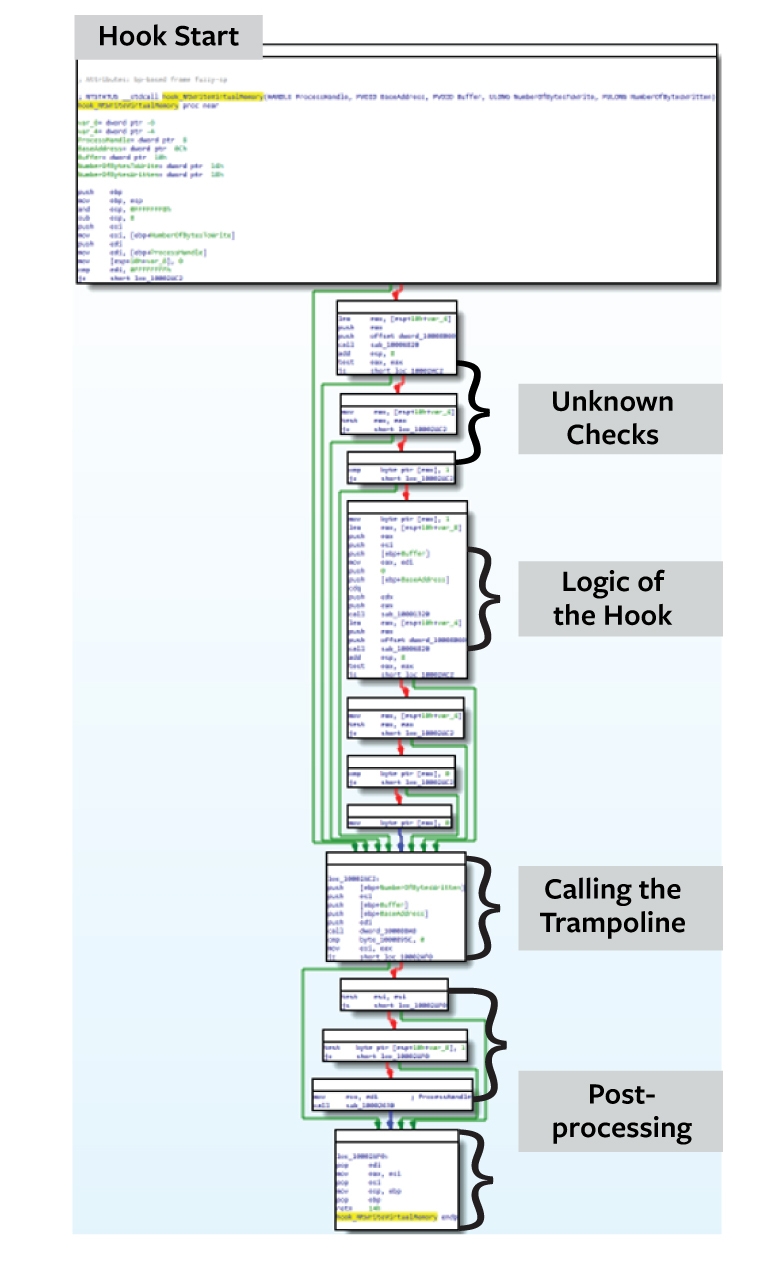

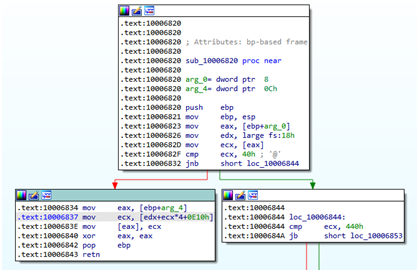

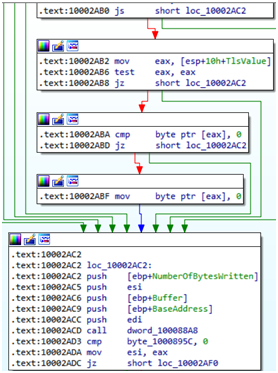

The hook looks like this:

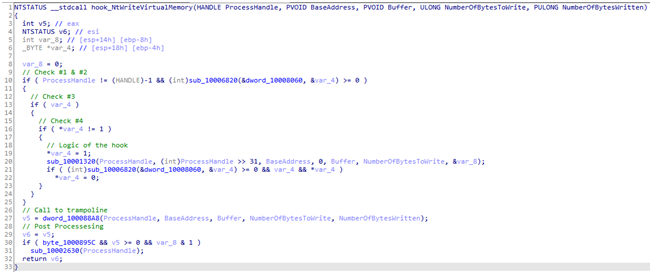

Here is the decompiled version:

As we can see, there are four conditional jumps being made before the hook logic starts. At least one of them should be the reentrancy check. If any of the conditions are met, the trampoline will be called directly, skipping the logic of the hook. As we see in the first screenshot, the first conditional jump checks whether ProcessHandle is a pseudo-handle (-1) to the current process. Since that isn’t very helpful, let’s see what the three other conditions are.

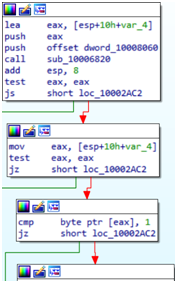

As we see in this screenshot, var_4 is a pointer to an integer. If sub_10006820 returns something other than 0x0, or if var_4 is NULL or the value inside var_4 is 0x1, a conditional jump will occur.

We can deduce that sub_10006820 sets the value of var_4, probably according to the value stored in dword_10008060. Let’s disassemble it:

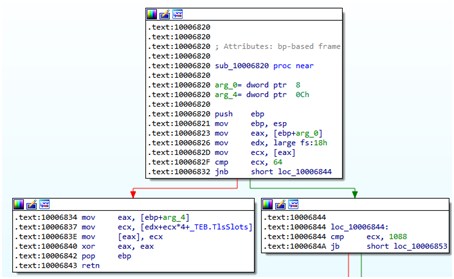

First, we know inside fs:18h is the TEB (Thread Environment Block), so after we added “_TEB” struct definition to IDA, we can now see something pretty interesting:

In 0x10006837 we see that ecx is using an index in the TEB’s TlsSlots member. This refers to TLS – Thread Local Storage (see note #1).

The TEB.TlsSlots array size is 64. But what if a program wants to allocate a TLS slot in the 65th index? In 0x1000682F, we see ecx being compared to the value 64. So, this translates roughly to the following C code:

if (*dword_10008060 <= 64)

*arg_4 = TEB.TlsSlots[dword_10008060];

In 0x10006844 ecx is being compared to 1088. IDA doesn’t offer any known constants for this seemingly arbitrary value. If we continue with the disassembly, however, this makes more sense:

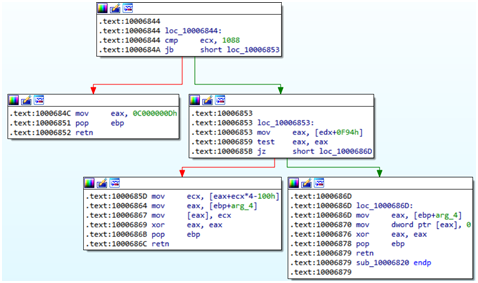

The instruction at 0x10006853 refers to edx again, which we know to be a pointer to TEB. This means that [edx+0F94h] translates to TEB.TlsExpansionSlots.

Going back to the previous question – if a program calls TlsAlloc() after all the slots of the TEB.TlsSlots array are already allocated, TlsAlloc() will internally allocate memory on the heap via RtlAllocateHeap() and set TEB.TlsExpansionsSlots member to that allocated memory’s address. This gives the thread an additional 1024 TLS slots it can use. If there’s an attempt to write to a TLS slot whose index is above 64, it will write to the allocated memory on the heap instead of the TEB.TlsSlots array.

So, now the number 1088 makes sense – it’s just the result of 1024 (number of available slots in the TlsExpansionSlots that are stored on the heap) + 64 (number of available slots in the TlsSlots that are stored directly inside the TEB). So, if the value stored in dword_10008060 is above 1088, it’s considered an illegitimate index.

While we may be tempted to propose a solution where our malicious program allocates all the 1088 TLS slots in order for this subroutine to return STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER, this solution isn’t possible because the vendor’s DLL allocates an index once it loads into the process, which is too early for us to intercept.

Back to the code – if the conditional jump at 0x1000685B happens, the value inside arg_4 will be set to 0x0. This roughly translates to the following C code:

if (TEB.TlsExpansionSlots == NULL)

*arg_4 = 0x0;

So now that we know how the value arg_4 is set, we can go back here:

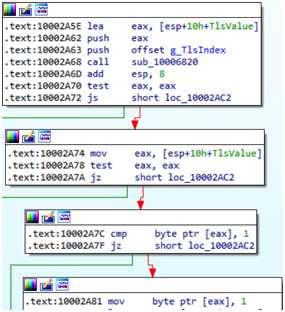

We now know that var_4 is the value stored in the TLS slot, so we’ll rename it TlsValue. We also know dword_10008060 is a pointer to a TLS index, so we’ll rename it g_TlsIndex.

This roughly translates to the following C code:

PDWORD TlsValue;

if (sub_10006820(g_TlsIndex, TlsValue) == 0 || TlsValue == NULL || *TlsValue == TRUE)

// Skip the hook’s logic

The instruction at 0x10002A81 sets the value stored at *TlsValue to 0x1. Later, we can see this value is set back to 0x0 (at 0x10002ABF):

To recap, the security vendor accesses a TLS slot via a global variable to store an address which points to a Boolean value, which, if set to FALSE will cause the code to perform the hook’s logic, and if it is TRUE, it will skip it and go straight to the trampoline. Once it finishes doing the hook’s logic it will reset the Boolean value back to FALSE.

Exploiting the Reentrancy Mechanism

If the g_TlsIndex is above 64, TlsExpansionSlots must be set to NULL so that TlsValue will also be set to NULL. If g_TlsIndex is 64 or below. TlsValue should be NULL or the Boolean value in the address stored inside of it must be set to TRUE.

Without knowing the value of g_TlsIndex we have no way of knowing which TLS slot to manipulate, so what should we do?

Our solution is to set all of the TLS slots and TlsExpansionSlots to NULL temporarily before a call to NtWriteVirtualMemory, and once we return from that call, we can restore all the TLS slots to their previous state. This is an easy solution that can be integrated with any malicious code; we simply have to slightly modify the source code of whatever offensive tools we want to use.

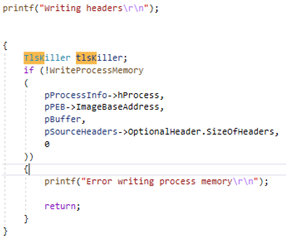

A more elegant solution would be to use a C++ object that will be allocated on the stack. What it will do in its constructor is back up the values of all the TLS slots and the pointer of TlsExpansionSlots and then set them all to NULL, and once its destructor is called then it will restore the original values of all of the TLS slots and the pointer of TlsExpansionSlots.

This action looks like this:

Whenever we want to call an API that we know is hooked, we will simply create a block of code around the call to that API. Creating a block of code guarantees that TlsKiller’s destructor will be called as soon as the hooked API is over. In our case we know that WriteProcessMemory ends up calling NtWriteVirtualMemory so we must put TlsKiller in the same block as WriteProcessMemory. For the sake of brevity one example is given:

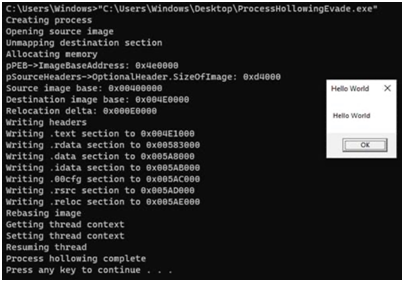

After re-compiling and running the executable, we get this:

No complaints from the Antivirus!

One Line of Code to Evade Antivirus

It seems that by simply adding one line of code before a call to a hooked API we were able to completely evade the antivirus tool’s behavioral analysis.

Depending on which attacks the antivirus aims to prevent with its memory heuristics it is possible to bypass whatever defense they will put up, as long as they use the same method of checking for reentrancy in their hooks.

Some antivirus products may devise their own methods to avoid reentrancy, and others might use TLS indexes too, which means they will also be susceptible to this attack. While they might do it differently (for example, not use the heap at all and just set the TLS slots as Boolean value or as an integer value), it will take very little effort to see if their hooks can be bypassed.

Other antivirus solutions might devise an entire mechanism altogether. It should also be noted that not all of the hooks placed by an antivirus have a mechanism to avoid reentrancy (for example NtProtectVirtualMemory is hooked but no check is done for reentrancy), so it is important to know which functions are affected by this.

Conclusion:

While Antivirus products have a high detection rate when it comes to known malware, they often prioritize stability first, requiring them to be compatible with edge-cases and overall performance. This lessens their security posture and opens up myriad possibilities for attackers. Therefore, a feature which was intended for stability can be re-purposed as a bypass method and open a path for intrusion and compromise. Further research will shed more light on which features of an antivirus can be abused.

If you’d like to learn more about Deep Instinct’s industry-leading approach to stopping malware, backed by a $3M guarantee, please download our new eBook, Ransomware: Why Prevention is better than the Cure.

Note #1: TLS Slots

TLS stands for “Thread Local Storage,” which some researchers might recognize by name as a known mechanism to run code before the PE’s entrypoint (TLS callbacks). This is, however, something else and unrelated.

Thread Local Storage is exactly what it sounds like – a place for threads to store their own local information in the TEB.TlsSlots array, which is an array of void pointers called TLS slots. Basically, that means that every thread has its own array which it can fill with values as it sees fit.

Since the mechanism is a bit more complicated than just accessing an array, there are 4 APIs that can be used for TLS:

TlsAlloc() – Allocates an index for the TLS. This index will be considered reserved and can be used by any thread to get and set their local values in their TEB.TlsSlots.

TlsFree(DWORD dwTlsIndex) – Releases the index allocated by TlsAlloc().

TlsGetValue(DWORD dwTlsIndex) – Returns the value stored in the thread’s TEB.TlsSlots[dwTlsIndex].

TlsSetValue(DWORD dwTlsIndex, LPVOID lpTlsValue) – Sets lpTlsValue as the value in TEB.TlsSlots[dwTlsIndex].

References:

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/procthread/thread-local-storage

- http://www.nynaeve.net/?p=181

- https://github.com/microsoft/detours/wiki/OverviewInterception